The Arnprior & McNab/Braeside Archives recently completed a project to digitize and make available online a range of primary records pertaining to Daniel McLachlin and the McLachlin Bros. Lumbering Co.

The project was funded by Library and Archives Canada and realized by Emma Carey, an archivist with the Arnprior & McNab/Braeside Archives.

As the website housing this valuable collection explains, "Daniel McLachlin, Esq. was an entrepreneur, politician, and lumber baron in the Ottawa Valley. In 1851, he bought 400 acres, including the derelict village of Arnprior, at the mouth of the Madawaska River, down which he brought square timber for export at Québec. Over the next few years, he relocated to Arnprior and developed the village. When the railway came in 1865, he built a lumber mill. By 1892, Arnprior was a town, and McLachlin’s boasted the largest lumber yard in the world."

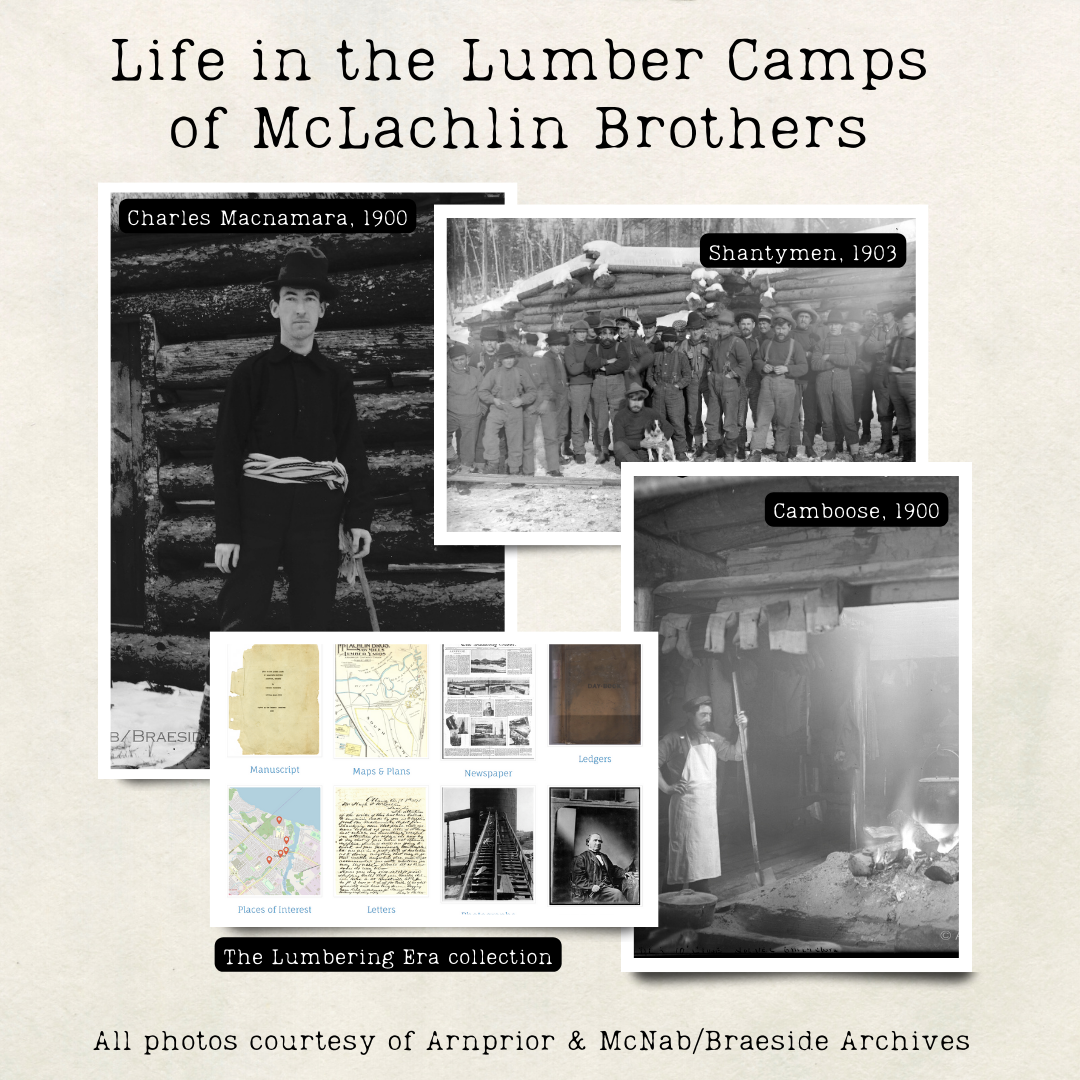

The Archives' newly digitized primary records document lumbering practices in the early 1900s in and around Arnprior and the Ottawa Valley. Organized by document type, the records include ledgers, maps, letters, photographs and a previously unpublished manuscript by Charles Macnamara. It was Macnamara's manuscript that caught my attention, and held it through its 144 pages. In his informative and entertaining Life in the Lumber Camps of McLachlin Brothers, Arnprior, Ontario, Macnamara offers rich detail of the lumbering enterprise.

To get a sense of the author, I read through the Arnprior & McNab/Braeside Archives' thorough introduction to Charles Macnamara, from the exhibit “Charles Macnamara – A Retrospective” created by Archivist Laurie Dougherty for the Community Memories Program of the Virtual Museum of Canada. It provides information from his birth in Quebec City in 1870 to his 48-year career with McLachlin Bros. in Arnprior and his life after that. At the age of 10, Macnamara moved with his parents—Richard Macnamara and Richard Hannah (Richianna) Parnell Macnamara—to Arnprior. From 1881 to 1921, Richard Macnamara served as the secretary and later secretary-treasurer of McLachlin Bros. Charles would follow his father into the business, starting with the company in 1885 and remaining with it until 1933.

A talented amateur photographer, Macnamara documented life in McLachlin Bros.' lumber camps in both pictures and words. The photos were taken between 1900 and 1908. The words were set down in 1940. He begins his narrative with this humble introduction: "This is something of what I remember of the lumber business as carried on by McLachlin Brothers, in whose office in Arnprior I began work on the 21st of December 1885 and have worked there ever since."

Macnamara describes every aspect of the lumber business in colourful detail, beginning with preparations in early fall for a winter in the bush: "The first stir in the shanty year was sending teams up from Arnprior early in September usually. These were the horses that had come down in the spring with their ribs showing after a hard winter's work, but had been pasturing all summer on the green fields of the Brown Farm and the Hartney Farm." A few teams of horses were harnessed to heavy wagons, hauling oats for the horses and limited supplies (the bulk of the supplies would be drawn on sleighs in the winter). Other horses were led on halters.

The men who worked in the lumber camps came from Arnprior and its neighbouring towns as well as from Ottawa. Macnamara writes: "Many men were hired around Arnprior and a fine lot of workers came from the surrounding country, from White Lake, Burnstown, Springtown, Calabogie, Renfrew and Eganville. Mount St. Patrick was noted for its tall Irishmen, all excellent shantymen. But the bulk of the hiring was done in Ottawa, which, even when it was known as Bytown, was the chief gathering place for shantymen from all over the country. Many came from the Province of Quebec, a considerable number from as far away as Gaspe, where they were fishermen in summer and worked in the shanties in winter."

Once in camp, the men were housed in shanties, sleeping in a double tier of bunks around three sides of the shanty. Macnamara describes the sleeping arrangements: "Each man was furnished with a pair of heavy gray all-wool blankets (for 30 or 40 years we bought blankets from no one but John Childerhose of Eganville who made the best shanty blanket in the country) and two men slept together. The bottom of the bunk was covered with small balsam boughs or hay. When balsam boughs were shingled over one another with the concave curve down they made quite a comfortable bed. No mattresses were provided."

The camboose cook prepared food in a camboose shanty. "With his simple open fire and his few utensils," writes Macnamara, "it was astonishing what well cooked food the camboose cook could set out. His bread, baked in the hot sand in a bake-kettle, was particularly good, close grained but light with a fine nutty flavor." The cook's utensils consisted of a camp kettle (a large pot hanging over the fire), a bake kettle and a tea pail. "Practically all shanty cooks made good bread," notes Macnamara, adding "if they couldn't they were soon fired." The food was simple but plentiful, with no limit on how much a man could take. "There was always boiled salt pork, often fresh beef, sometimes potatoes and cabbage," notes Macnamara. "The standard breakfast dish was baked beans." There was no dining table in the camboose; the shantyman balanced his tin plate on his knee and placed his tea dish on the bench beside him.

With evolutions in cooking methods, the menu also expanded, explains Macnamara. "The stove-cook soon displaced the camboose cook and in a few years, it was hard to find a man who knew how to cook in the sand. The bill-of-fare was enlarged with the better cooking facilities of the stove, and pies and cakes appeared on the table. Jam, figs, and cheese were added to the menu."

The remainder of Macnamara's manuscript covers all roles in the lumbering business—from logmakers, cullers, clerks and agents, to road cutters, teamsters, drivers and sorters—as well as the people and places he encountered, often with humorous remarks. Much of the manuscript consists of stories supported by photos, making for an easy, engaging read.

"Charles Macnamara died in December 1944 at the age of 74," concludes the Archives' introduction to Charles Macnamara. In 1959, Macnamara's niece—identified as Mrs. Franklin Cunningham—lent her uncle's manuscript to Ontario Archives. Today, anyone interested in an account of life in a lumber camp some 125 years ago would enjoy reading Macnamara's vivid recollections and viewing his superb photos.

I would like to acknowledge the support and guidance of Archivist Janis Hernández with the Arnprior & McNab/Braeside Archives. Without her help, I would not have been able to bring this post to life.